Blank Mirrors

Inside a new Warhol exhibition, plus a beautiful new book on Brutalism, and part 6 of non-fiction writing course Couch to 100k.

Dandy Warhol

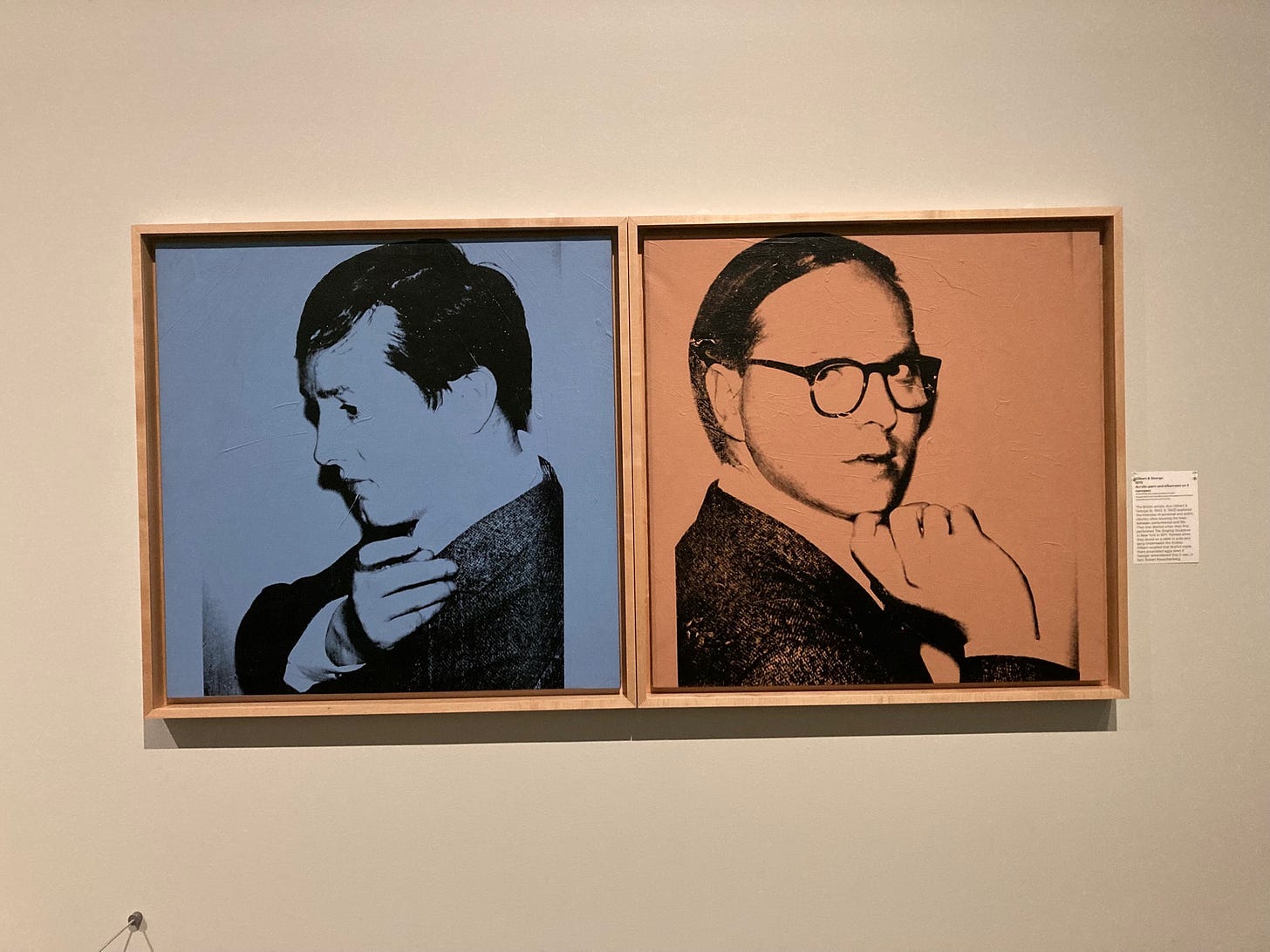

No matter how familiar I feel with his work there’s always something miraculous about Andy Warhol. While it’s easy to boil his art down to a campy critique of consumerism, celebrity and sensation, that often feesl like a denial of the actual work itself, no longer allowing it to be as beautiful or ugly or discomforting as it actually is in reality. Those screen printed portraits of Elizabeth Taylor or Marilyn aren’t superficial – or aren’t just superficial. They seem to pull the subject apart, colour by colour, feature by feature, taking the language of beauty or celebrity gossip and making it ugly or distant, harsh or dispassionate, so it’s all about the viewer, with the subject deliberately made alien.

A new exhibition of his work at MK Gallery takes moments of his work and life and brings them together in a way that feels more intimate than the usual epic Warhol show. Here with a less comprehensive approach it’s easier to see his awkward attempts to make himself as flat and blank as these screen prints, through drag makeovers or awkwardly frozen images. And it’s easy too to see the journey of how he goes from observant outsider to ending up as famous as his subjects, so that by the time of Haring and Basquiat he may think they’re a gang all on a level. but his fame is distorting those relationships, just as his portraits distort the faces of Mao or Jagger.

Towards the end of the show it features a wonderful written passage on what he sees in the mirror: the blankness and kitsch that consume him, and the more troubling realities of his pale and tired flesh too. And it’s in that gap that this exhibition frames his work, so that his war paintings of army boots and Soviet nuclear missile bases sit on cow print wallpaper; electric chairs beside Marilyns; AIDS benefit posters beside celebrity portraits. And we can glimpse in so many of his portraits of other artists - Gilbert and George, Joseph Beuys, Robert Mapplethorpe among them - how exposing and distracting the celebrity that comes with being a celebrated artist must be, and also how distancing.

There’s something thrilling about seeing this work in the flesh, not in the imposing setting of a major museum, but in an intimate and informal space like MK Gallery, who do a great job of bringing out the human themes in his work over the mass production. Here the works seem to lose their distance but not their mystique, feeling as magically charged as they must have seemed before the construction of his persona and fame made it all seem so inevitable, giving him the fame he wanted but also somehow robbing his work of any sense of its creation.

One of the most curious images is a portrait of Barry Goldwater, right wing precursor to Reagan and the new right in the US. Goldwater would lose the election to LBJ spectacularly in 1964, but would remain a figure of inspiration to the slash-and-burn libertarian wing of the Republican party. But his liberal attitude on social issues - on homosexuality and drugs - would put him widely at odds with the Christian right that Reagan so embraced and which has held sway ever since the rise of the Tea Party in the US two decades ago. The picture’s caption remarks how Goldwater came and introduced himself to Warhol, and how the artist found the white-haired man handsome and charismatic, the two seeing something in the other they could work with: Goldwater Warhol’s celebrity and wealth and self-made image, Warhol Goldwater’s faded glamour, someone who had scaled the highs and lows of American political life, and could be reduced down to a shock of white hair, cheekbones and a sense of restless unfulfilment.

Shadows of violence and death hang over much of the show, his ‘disaster’ images of electric chairs, race riots and revolvers every bit as significant as his celebrity portraits. It’s the combination of these themes and worlds that gives the show weight. As the US strides into a new era of belligerence, warped celebrity and chaos, this show connects us back to strange brittle moments from its past, when the brashness of an outsider’s eye could be refreshing, and studied ignorance could be a shocking way to unlock the mysteries of power and status, and not a way of brutally wielding it. But most of all, it’s the way the exhibition has, as you progress around it, of slowly unlocking a sense of the man that makes it feel refreshingly un-canned.

The exhibition has just opened at MK Gallery Milton Keynes.

Rubs knees

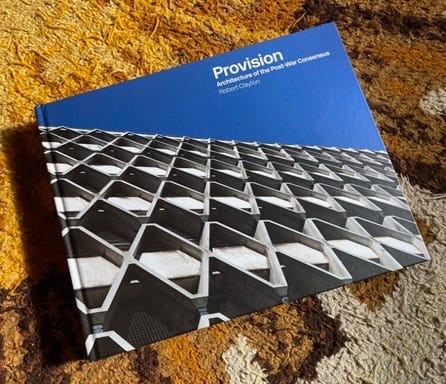

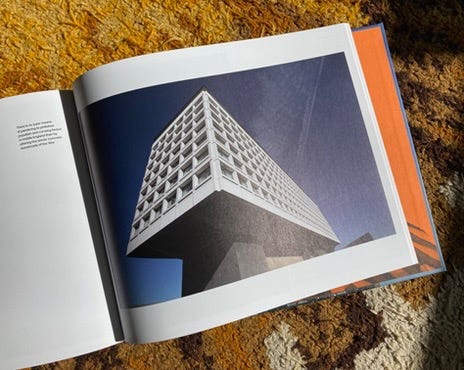

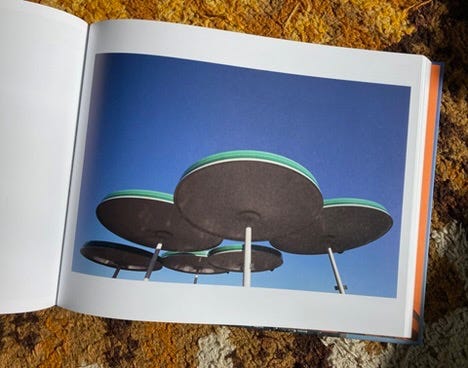

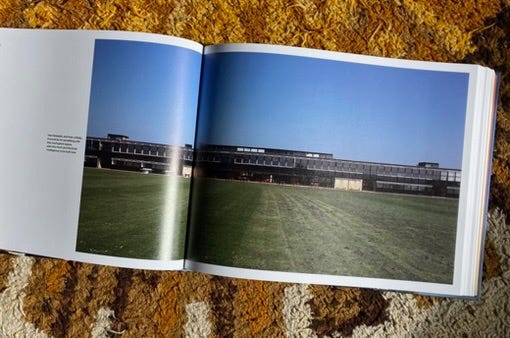

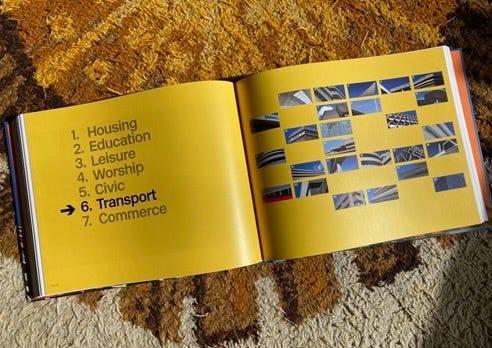

This week I had a delightful treat, the new book by photographer Robert Clayton, Provision: Architecture pf the Post-War Consensus. He previously recorded the life of Lion Farm Estate in the west Midlands in his book Estate, but here has gone from the local and specific to the national and all-encompassing. And rather than the street photography of Estate, Provision offers instead clean, bright, heroic shots of modernist buildings from his travels, a kind of gazetteer of our distant space-age British past. The most remarkable thing about te book is how it’s reminder of how many post-war buildings of quality remain, which is easy to forget in these ideologically opposed times. As a celebration of their presence, the book really shines by spotlighting the multifarious roles they play: transport hubs, schools, housing estates, car parks, churches, shops, civic centres. This is a whole world that was built, connecting to older towns and now to newer dreams too. At over 300 pages of ravishing photos beautifully repoduced, Provision captures the excitement of each building, and as such is a concentrated burst of post-war sunshine. Which is what the world needs right now. You can find out more here.

Radio On

This Sunday, 7:15pm on Radio 4 Owen Hatherley presents a half hour documentary looking at Colin Buchanan’s long lost Solent City Plan, for a vast linear city joining Southampton to Portsmouth. The Story of Solent City uncovers this little remembered mega-plan, and tries to unpick what it might have been like, and why it never came to pass. I was lucky enough to be interviewed for the documentary, to talk about how Milton Keynes encapsulates many of the linear city ideas of the era, and how it gives us a glimpse of the south coast city that never was. You can listen to it here, when it’s up.

Also a few months ago I was in conversation with photographer Simon Phipps about his books, from Brutal London to Brutal North, at MK Lit Fest online. If you missed it but would like to see us discussing some of his amazing images, they have uploaded it to YouTube here. Simon’s most recent book, Brutal Wales, has been shortlisted for the Architecture Book Awards.

Tips for non-fiction writers #6

I realise this is a bit of a slow burn, but then so is writing a book, and having thoughts percolating around for a while can be very helpful. Though, of cours,e you do have to get down to it at some point. But in the meantime, following on from last month, when I talked a bit about grand narratives, this time I’m going to focus on some different, les classical, ways of structuring a non-fiction book. After all, they can be non-linear or episodic, or a combination of the two.

Non-linear narratives use some elements of the grand narrative, except here you’d typically be putting the events out of order to allow more artful construction. To do this you need to be very familiar with your material, which will give you the necessary confidence when handling it. These sort sof stories can of course take many forms. Non-linear narratives can allow you to attempt parallel storytelling, for example: telling two or more different stories side by side, rather than consecutively, which can be a handy device when dealing with complex narratives over different time periods, or for events happening simultaneously; or just as a way of bringing two otherwise disjointed and unconnected narratives together. It can also allow you to write a ‘constellation’ narrative, where different points are of equal import. Or fragmentary narratives, where you are not swinging to some huge story arc but instead focussing on a story that may have no easy conclusions or shape. Writers particularly good at this more impressionistic form are Robert Macfarlane and W.G. Sebald, where the allusions and shadows are allowed to rule over the literal.

One of the issues with non-narrative storytelling is that unless carefully handled it can seem a bit chaotic or confusing to the reader. Keeping the reader’s attention and making them understand what is going on is a challenge at the best of times, and these more complex structures can pay off wonderfully in terms of dramatic reveals, intellectual stimulation and satisfying links, but do require a lot of work. How do the stories or fragments relate? Do they need signposting and linking, or are you happy with the disjunct?

What could it add to your writing? Well, it can help you position revelations and narrative moments, while more sequential storytelling usually dictates were these fit. It can give the book a sense of energy and originality, and help with developing your unique voice. It allows you to explore simultaneous moments or connect moments or people that otherwise might be far apart in your narrative, if you’d placed them more conventionally chronologically, or in different sections.

People talk a lot about circular narratives, but in a book this is an illusion. Your reader is unlikely to be starting the book at a random point, they will generally read from beginning to end (if we’re lucky). But you can certainly play with circular motifs, events and themes. The book can take you back to the start, cycle back over the same events to reveal new meanings and facts. It can be hugely satisfying a sa reader to return to themes or evenst played out earlier in the book, but with added knowledge or insight.

You can also use a single moment to branch out from. This is a non-linear technique that seems to be particularly popular at the moment. True crime books often use this as a technique, as do books deconstructing everything from songs or single historical events. From there you can branch into several simultaneous narratives, or keep circling back to revisit it with fresh eyes.

Then, related to non-linear narratives, are episodic structures, which are brilliant for geeks. They work well for subjects such as pop culture, science, self-help, books on obsessions or multiple linked topics. They can be lighter (not necessarily in tone, but in narrative weight, as the reader can focus on that one episode rather than having to remember events/characters from 200 pages ago to make it work). It’s a more flexible way of approaching the construction of a book, but it still needs to be focussed. Episodic books are not books of seperate essays, they are as artfully constructed as any other narrative, and so careful attention needs to be paid to the cumulative effect of these episodes, how they add up, what you reveal when. They need to feel collective as well as cumulative, so in that sense they also play into the story arc of a grand narrative, just not as overtly. They still need a great ending and intro to do a lot of the heavy lifting, and to knit together your themes and ideas.

Some excellent episodic non-fiction books I’ve enjoyed have been Travis Elborough’s seaside book Wish You Were Here, Martin Gayford’s story of the British post-war art scene, Modernists and Mavericks, Jon Ronson’s knockabout investogation The Psychopath Test or Craig Brown’s book of glimpses of Princess Margaret, Ma’am Darling.

Non-linear narratives are useful if you’re not attempting to be definitive. But tying them together can feel like the big challenge. Stand-up comedians use a method of call-backs, where you seed ideas early in a set and then keep returning to them later on, with bigger and bigger laughs each time as the audience recognises and appreciates the effect. It makes the whole set feel more rounded, without having to have some heavy plot apparatus to hold it together. Non-fiction books can really benefit from a similar approach, of lightly holding your material together and rewarding he reader with ‘easter eggs’ as they go along.

The final form I wanted to mention was another popular one, the quest narrative, which is a subset of the episodic. You’d find this in most travel and nature writing, investigative journalism, sports books, and more and more, in humour writing. They tend to have a memoir-ish slant and require the author to be in the book rather than an omnipotent voice. You need to put yourself at the centre, and make sure it feels grounded in reality. In a quest narrative you need to set up the aims of the experiment at the start and pay them off (or not). Katherine May and Raynor Winn manage this beautifully. You don’t always have to have all of the answers. Sam Knight’s The Premonitions Bureau is a great example of a quest that can never be solved, but which is hugely satisfying nonetheless because that comes from the weirdness of the story he’s telling.

Chapters can be seen as tasks to be achieved (a place visited, a meeting made, a vital piece of evidence found, a memory explored). But they can feel artificial or forced. Sometimes you can play that up, of course, for effect. Sometimes the personal quest element can end up looking slightly absurd. You need to step back and ask yourself, will anyone else care?

Some books seem to be all of these things. Pete Brown’s book on working men’s clubs, Clubland, is a grand narrative, a personal quest and episodic. He had enough material that told a big story, and also enough individual stories to create episodic chapters, plus enough personal connection to make it feel authentic.

One of the great non-linear storytellers was David Lynch, whose films often jump around and defy logic, sneaking into our subconscious instead reaching for more everyday forms of sense. He once said that his preferred method of coming up with scenes for a film was to sit in a cafe with 50 blank note cards and plenty of strong coffee (he didn’t mention cherry pie, but you get the idea). He would then write an idea for a scene on each of his cards, and when he had filled them all up then he had a film. And that helps us understand where the uncanny sense in his films originates.

EXERCISE. Planning the David Lynch way. Let’s imagine your book has ten chapters. Come up with ten important events/topics that need to be covered in your book (eg stages of a life, places, people, historical events). Each of these will form the basis for a separate chapter. Then, look at the result. Do they seem to form an obvious grand narrative, with a beginning, middle and end? Is that too safe and predictable? What happens if you run them backwards, or swap the odds with the evens? Does that show new connections are possible?

See you next time.

I enjoyed looking through the Robert Clayton book this weekend - a few buildings I wasn't aware of and added to future itineraries around these isles. Thanks also for the glowing Warhol review - I'll definitely make the effort to visit.