This week I had the pleasure of catching Modernism, Inc.: The Eliot Noyes Design Story, a documentary film combining some of the things I find most endlessly fascinating: mid-century design; utopian modernist thinking about how we as people and societies function; and the clash between contrasting ideas in the sixties and seventies. Writer-Director Jason Andrew Cohn made this film in 2023, though I only just got to see it as part of the All Flows design festival at MK Gallery, organised by the always busy and inspiring Pooleyville art collective.

Cohn has previously directed the documentary Eames: The Architect & The Painter, and so this feels like it is part of a bigger project, to put the context back in the US fascination with mid-century modernist design. And certainly Modernism, Inc. is full of cameos by significant figures: Walter Gropius, Noyes’s tutor; his collaborators Charles and Ray Eames; cinematic legend Saul Bass; and fearsome, sweary art director Paul Rand.

The documentary is a series of culture clashes: Noyes vs the military in WWII, who refuse to take his glider programme seriously; Noyes vs the old guard at IBM, who refused to update; and Noyes vs the hippy radicals of the late sixties, who would challenge all of the concepts he had been expounding, and who would reject the clean-lined mid-century vision of corporate America. Well, until they later became it, of course. It reminded me of that line in Don Henley’s sublime single of 1980s nostalgia, The Boys of Summer, seeing Grateful Dead stickers on a Cadillac, which represents how hippy idealism sold out to big money.

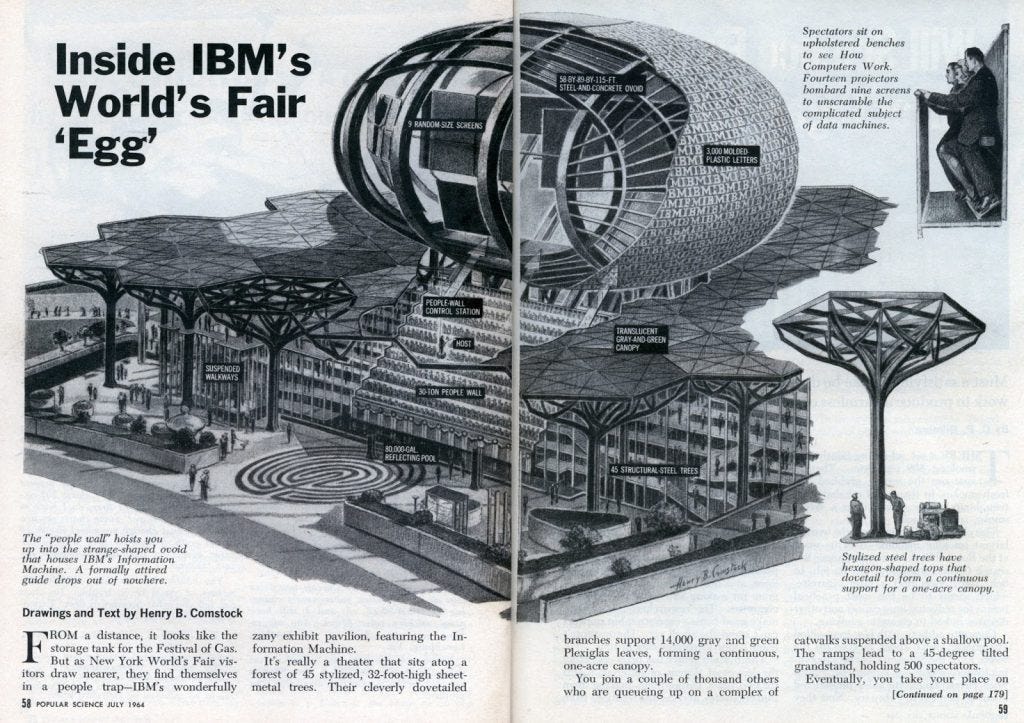

It’s fascinating getting a glimpse into how Noyes injected energy and focus into IBM, whose hardware had the whiff of Edwardian Singer sewing machines more than the computer technology it was actually producing. And astonishing we have footage, shot by Noyes’s own son, of a fateful 1970 design conference invaded by hippies and radicals intent on shaking these design gurus out of their complacent corporate bubble. The documentary is fairly soft on the subject matter, but insightful and thoughtful rather than full of snappy angles, which is always a relief.

Hoping it comes to a streaming service, or even better, an art cinema near you.

Port Loop claims to be Birmingham’s ‘best place to live’. Best for whom?

Up at Edgbaston Reservoir, 81-year-old Tony Hutchinson is staring out, not at the vast, still expanse of water, but down the hill over the industrial ruins of Ladywood, and the sprouting roofs of a new modular block of flats.

Recently wrote this piece for the Birmingham Dispatch on Port Loop, one of the industrial areas along the canal being turned into new housing, this time by Urban Splash. I think you might need to be a subscriber to read it, but perhaps you are, what do I know?

The dead hand of data

Shhh everyone. It’s another one of those bits on writing he does, like he knows things. Don’t make eye contact.

One of the big things to be aware of in writing narrative non-fiction is the dead hand of data. Sorry data nerds, but it’s true. Data is your book’s underwear and you don’t want it to go out with its pants showing. Data could be your research process, legal documents, the material you’re using to synthesize together or numbers you’ve culled from reports and databases. It’s the notes you’ve made, the references you’re bringing in, the stuff that underpins your thought process, things you’ve found that bolster your idea. It’s easy to become beguiled with these totems of great power, to become beholden to them as if they are precious objects to be presented in their own right, rather than the things to be written into (and sometimes out of) your draft.

But how do you spot if you’ve become the prisoner of data? Read your work back. Are you overexplaining? Knowing how much to trust your reader is always a tricky judgment call, but there are some ways you can spot if it’s going a bit wrong. Are you so into the idea of explaining concepts that you’re explaining such everyday things that literally every one of your reader will know and be bored by? It’s so easy to do, once you get into explainy mode, I’ve done it every time I’ve written a book. You just need to sense check it. Is this the right level for the reader I’m expecting? Too intense and detailed? Too hand-holding? Or just interesting and light enough to guide them through?

So how do you avoid the dead hand of data? Well, firstly, when you’re thinking about a big section coming up that needs to explain something, can you dramatise your point? Or can you step back, and reveal a bigger picture by not being too swept up in the detail? Or reveal that bigger picture through detail?

It’s here you need to remember you’re storytelling, being entertaining as much as you are informing and educating. There’s a reason Horrible Histories were so successful. Bringing a subject to life in unexpected and fun ways can be a really rewarding way of approaching complex and arcane topics. Never forget you are a writer first and foremost, and your gift to your reader is your ability to communicate your subject in the most diverting way possible, not just to get all the information down on paper. Even though a first draft may be exactly that. If you find it fun or fascinating, so will someone else. If you find it boring, then it probably is, and you might need a new angle to bring it to life. Remember, to be serious is not to be dull. Your writing can feel transgressive, fun, exciting. But only if give yourself permission to play with the elements.

Think of a writer like WG Sebald, whose entire strategy seems to rely on diversion as a way of getting to the truth. Rarely does he ever relay a story from history or art directly, usually they are smuggled into the prose by some circuitous route. And as the reader often you forget why you’re here, being led into this curious byway, but that’s because the writing itself is so enchanting or deeply human, and the things you’re being told so interesting that you’re not drumming your fingers wishing it would hurry up. He leaves you with the feeling that you wish it was longer.

EXERCISE: Find a piece of research you have dug up for your project – complex stats, a byway in history, a legal, philosophical complexity, the more unpromising and indigestible the better. Now, think about the person you’re writing for. Not the other books they read, but the TV or film they might love. Now imagine this information was being dropped into their favourite crime drama or comedy, as a relevant piece of information to help the plot along. How might the characters in that talk about this information? Would one of them make fun of it, another pull it to pieces, one more try to make wild connections to other things from it? None of them would plod through a long and detailed monologue, it would be broken up in zippy dialogue and conflicting opinions and voices. Now write a short scene where your piece of research is being discussed by two of your favourite TV characters. I’m thinking David and Alexis in Schitt’s Creek, but then that’s always what I’m thinking. Give yourself half an hour and have fun with it, let the characters show you a new and unexpected way to talk about this dry piece of information, until it’s, as Alexis would say, so cute.